The Tragedy of Audrey Munson

Forgotten.

It’s April 14, 2022 — 110 years to the day after the sinking of the Titanic. There are memorials to the lost grandeur of the great ship everywhere in New York, and one of the most subtle is the Isidor and Ida Straus Memorial, located at Broadway and 106th Street. (If you’ve seen James Cameron’s Titanic, the Strauses were featured in one of the movie’s most poignant scenes — an elderly couple in their evening finery cuddling on a bed together as the water rose around them.)

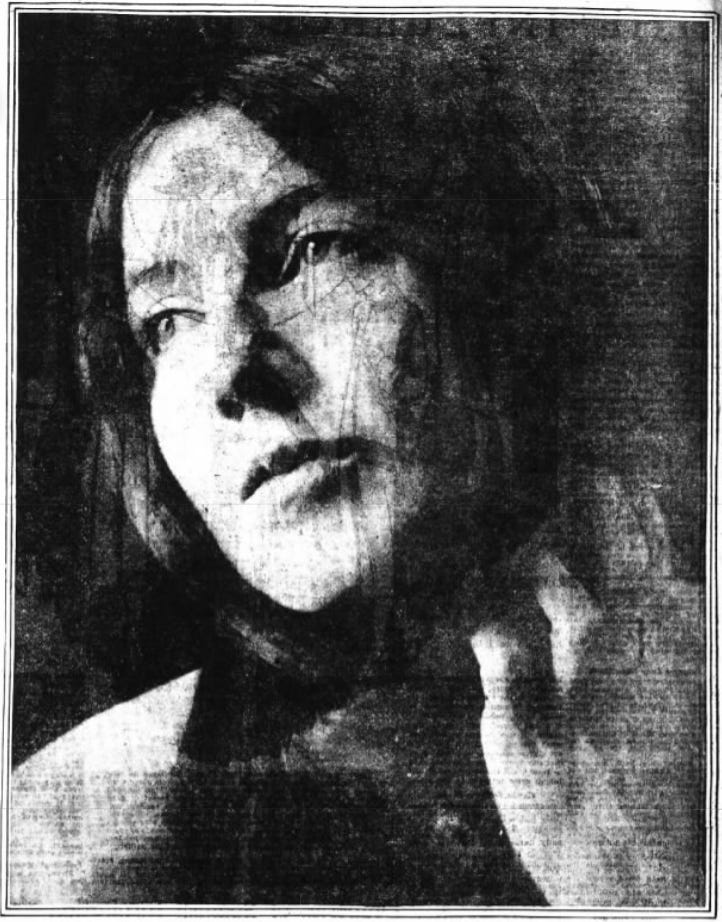

The Straus Memorial was installed on April 15, 1915. The bronze sculpture at its heart is a beautiful, long-limbed woman in a flowing Grecian gown gazing sadly into what today is a garden, though for years it was a reflecting pool. Sculptor Augustus Lukeman created the figure. His model was Audrey Munson. In 1915 she was considered the most beautiful woman in the world.

The figure in the Memorial is called Memory. There’s a rich irony in Audrey Munson’s form being synonymous with memory.

Audrey Munson is everywhere. You’ve seen her figure dozens, maybe hundreds of times, and likely had no idea. She was the first supermodel, though her fame was at its zenith before we relied on cameras alone to commemorate great beauty. Men, always men, engraved her curves in marble, granite, and bronze — and on film, though most of the movies she starred in are lost today.

She was called Miss Manhattan for a reason. In addition to the Straus Memorial, you can see her in the Monument to The Maine outside Central Park. She modeled for sculptures found today at the Brooklyn Museum and in the U.S. Customs House, and countless other places.

Audrey Munson was born in 1891 and moved with her mother from upstate New York to Rhode Island after her parents divorced when she was eight years old. She later moved again with her mom to New York City and, at 17, began a career as a chorus girl. She might have had an admirable career just doing that, but photographer Felix Herzog discovered her, and he was her entry into the world of fine art.

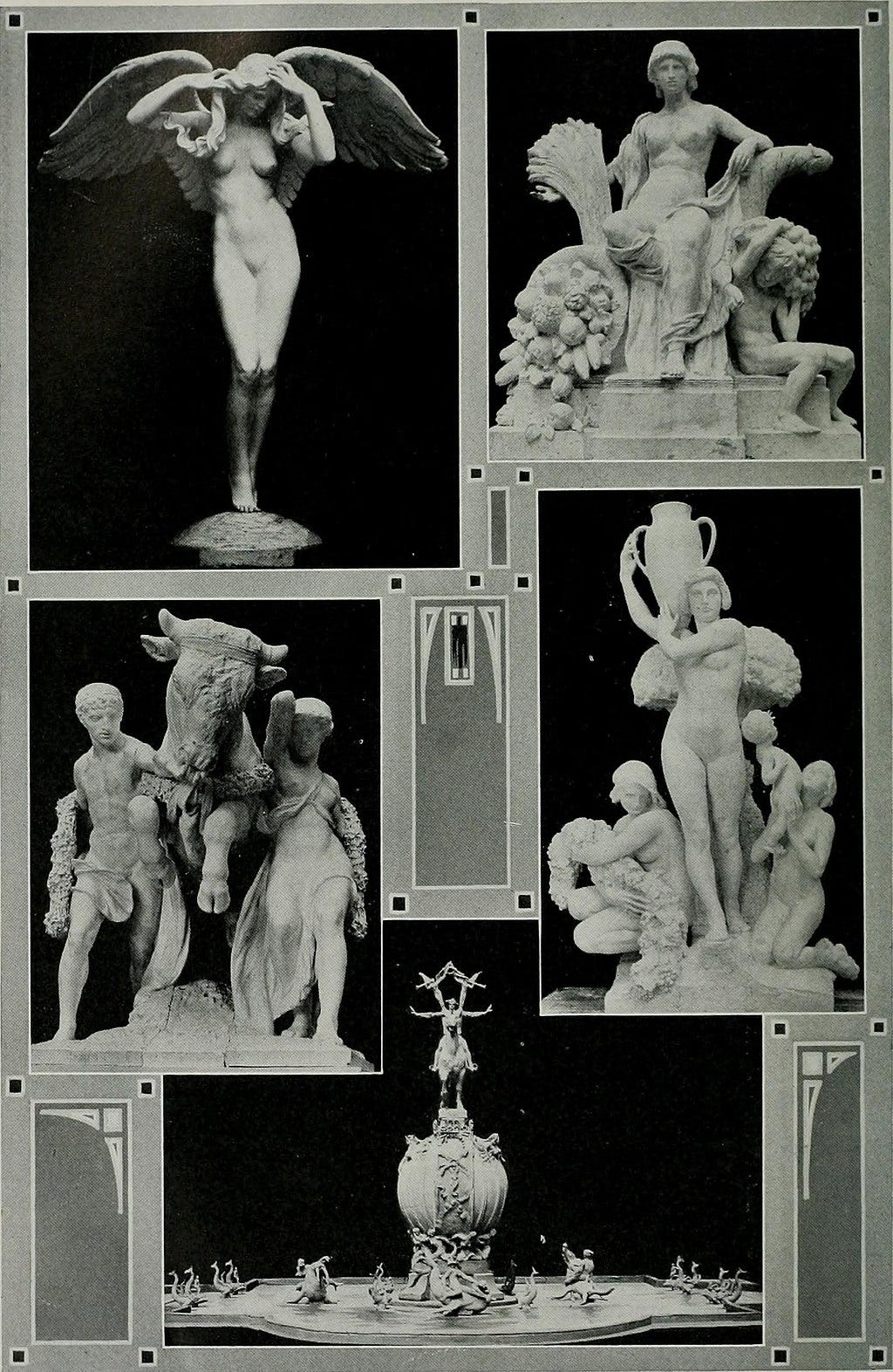

Munson was so popular that by 1915 sculptor Alexander Stirling Calder was using her as his model for the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. She modeled for three-fifths of all sculptures produced for the event, leading to another nickname: "the Panama Pacific Girl."

For a long time, Munson’s appearance as an artist’s model in the 1915 movie Inspiration was considered the first instance of an actress appearing nude onscreen in a mainstream movie, but it turned out to be the second time. While film censorship would go to extremes in the 1930s, censors in 1915 didn’t cut Audrey Munson’s scenes because they reasoned that they’d also have to censor great Renaissance art.

In 1919, Munson was nearing 30, and things were changing for her. She wasn’t getting much work, and her life was quietly unraveling. Earlier that year, she wrote a strange letter to the State Dept. denouncing a wealthy man (her mother claimed Audrey was married to him, but no one ever found proof) as pro-German — a terrible thing to be in 1919. Then Dr. Walter Wilkins, a white-bearded married man more than 30 years her senior, killed his wife, Julia. Many believed he did so to be with Audrey Munson.

Wilkins and his wife Julia owned a boarding house at 164 West 65th Street in Manhattan. Munson lived there with her mother.

On the night of February 27, 1919, police in Long Beach, N.Y., received notice of a robbery and murder. They arrived to find Dr. Wilkins kneeling beside a bloodied Julia, wiping her face. As police arrived, someone witnessed Julia waving her hands over her head and muttering, “Don’t hurt me.”

Dr. Wilkins’s suit was bloody. He said three robbers attacked them, striking him on the head before battering his wife. His derby was crushed, but Wilkins appeared otherwise unharmed. Julia sustained 17 blows to the skull.

In his 2016 book about Audrey Munson, The Curse of Beauty, author James Bone quoted Dr. Wilkins’s account of the crime:

I was about to walk up the steps when I noticed the door of the garage was open, and becoming suspicious I told my wife to wait at the door while I made an investigation. Just as I entered the hallway I was hit on the head with a blackjack by some man who said he would not strike again if he was handed over all that I had in my pockets. While I was being searched, I heard my wife moaning and calling for help. The man who had taken the contents of my pockets ran out and down the road. I then went inside and found my wife lying in a pool of blood.

Police worked throughout the night looking for the assailants. They checked under bridges, on departing trains, and in local boathouses. Long Beach police chief Patrick Tracy began questioning Dr. Wilkins the following morning. Asked about the robbers’ appearance, Wilkins said “they looked like regular New Yorkers,” which struck the chief as odd. So the chief examined the area where the aging physician said he’d fallen after being hit. Tracy, who spent more than 30 years with the NYPD before becoming the top law enforcement official in Long Beach, realized there was no way robbers could have stepped over Wilkins’s fallen body to get away. Instead, he would have blocked the door.

Chief Tracy’s experience told him that the way Julia was attacked made little sense — why repeatedly batter her with a lead pipe or padded hammer rather than grabbing her throat to stop the sound? Things weren’t adding up. The condition of the home seemed telling too. The couple had multiple pets, including a parrot and a monkey, and their house was generally disorderly and dirty. It was the kind of place most robbers wouldn’t bother with — or create obvious evidence of new disturbances if they did break in. Chief Tracy knew Dr. Wilkins was lying. So he called off the search for Julia Wilkins’s killers. He knew the killer was the white-bearded physician in front of him.

Evidence began to mount. Investigators matched the paper wrapped around the hammer that killed Julia to a copy of the Lynbrook Era, a local newspaper, found in one of Dr. Wilkins’s old suits. His prints were on the hammer. In addition to this and other evidence, a New York police officer said he remembered a past conversation with Wilkins in which the doctor had queried him closely about the details of a similar crime, particularly about the wrapping of a bludgeon in cloth to quell blood splatter.

Police still had to build a case, though, and they planted a female detective as a boarder in the Manhattan house where Audrey Munson lived with her mother. The investigator befriended the housekeeper there, who was happy to reveal details that only kept the spotlight on Walter Wilkins — including further information about the attention he’d paid to the model.

According to The Curse of Beauty, Dr. Wilkins’s stepdaughter told police that he warned Munson to never “get married because if you do, you’ll lose your symmetrical figure.” And among his personal effects, police found a postcard-sized photo of Audrey in a swimsuit.

Perhaps stranger still, Audrey Munson and her mother Kittie had left the address weeks before Julia Wilkins was murdered. Police wondered if they had some kind of love triangle on their hands.

About a month after Julia Wilkins was murdered, the New York Times reported that “Audrey Munson, said to be a motion picture actress and artists’ model, and her mother are being sought by District Attorney Weeks in the hope they may be able to give valuable information concerning Dr. Walter Wilkins, according to county officials today.”

Private detectives eventually found Audrey and Kittie Munson in Toronto. But they refused to come back to the States.

It seemed at first like Dr. Wilkins was out of the medical business — that he lived on his wife’s money, and his main job was managing their properties. But it turned out he was Broadway’s Dr. Feelgood, prescribing morphine to theatrical clients at odd hours over the phone. He also prescribed it for himself. Audrey would admit he had been her “medical adviser,” but she also said she “had only the slightest acquaintance” with the accused, speaking in passing and “nothing more.”

She fought back in true diva style, sending a letter from Canada to Charles R. Weeks, the prosecutor in the Wilkins case. “Dear Mr. Weeks,” she wrote in part, “I have been much annoyed by statements in the newspapers that you were looking for me as a witness in the Wilkins murder trial.” Then, regarding Dr. Wilkins, she wrote, “And let me say right here that I am not going to be cajoled to coming to [New York] to testify against old Dr. Wilkins, because mother and I believe him to be innocent of any crime, as we know him to be a gentleman, incapable of such an offense as charged against him.”

“The relations between Dr. and Mrs. Wilkins were ideal,” Munson’s letter continued, “and during the time mother and I lived with them we never knew them to have a fight.” She explained that she and Kittie had left the boarding house owned by the Wilkinses to sail to England on March 1 but had “received notice that there was trouble about my films in Canada, and my mother and I immediately went to Toronto.”

Eventually, she got to her point: “There was never anything wrong between Dr. Wilkins and myself. On several occasions, he acted as my medical adviser. Very truly yours, Audrey Munson.”

Munson and her mother also sent affidavits to New York via the private detectives who found them. They met a much more curious fate than the letter Weeks leaked to the press. As James Bone tells readers in The Curse of Beauty:

The content of those affidavits has never been revealed—and the entire court file has gone missing from the Nassau County Courthouse despite the enormous gravity of a capital murder case. The press described the affidavits as “sensational.” An unnamed Burns Agency detective told the press: “The contents could prove very damaging to the defendant.” Yet they were never used in open court.

In the end, New York did not need Audrey Munson’s star power in the courtroom. A jury convicted Dr. Walter Wilkins of murdering his wife Julia and sentenced him to the electric chair.

The Sunday before Wilkins was to be transferred to Sing Sing to await his execution, he was found hanging from a pipe in the bathroom near his holding cell. He died wearing a cutaway coat and vest, starched collar and tie, dark trousers, and polished dress shoes. The doctor said he was “absolutely innocent” of killing Julia in the notes he left behind. He also said he preferred to be his “own executioner.”

A year later, a bedraggled woman attempted to place a death notice for Audrey Munson in an upstate New York newspaper. She didn’t fool the clerk taking the request. “Dead? Why what are you doing, putting over a press agent stunt? I know you, Miss Munson.”

It was Audrey, and she thought the way to restart her life was to announce her demise and begin anew under another name. Thanks in great part to the Wilkins case, she had been cast out of high society. She wasn’t the toast of Newport's nearly-royal American titans of industry. Her star had fallen, but the worst was to come. On May 27, 1922, she tried to commit suicide by dosing herself with mercury bichloride.

She survived the attempt and spent the rest of the 1920s attempting to claw her way back into fame. Still, Audrey Munson became a sadder figure with each newspaper article, and yellow journalists and dedicated muckrakers alike were always compelled to underscore how far she’d fallen. Finally, in June 1931, her mother Kittie petitioned for Audrey to be locked away in an insane asylum.

So Miss Manhattan, the American Venus, the Panama Pacific Girl, entered St. Lawrence State Hospital for the Insane in Ogdensburg, New York. Doctors there diagnosed her with depression and schizophrenia.

She remained in St. Lawrence, forgotten, until her death on February 20, 1996.

Audrey Munson was 104 years old.

So she spent approximately 65 years in a hospital for depression and schizophrenia, holy crap.